Urban plants' phenology is being severely disrupted by city lights that are on all night, changing when their buds develop in the spring and when their leaves change color and fall off in the fall. The growing season in cities is increasing, according to new research, and this can have an impact on anything from allergies to local economics.

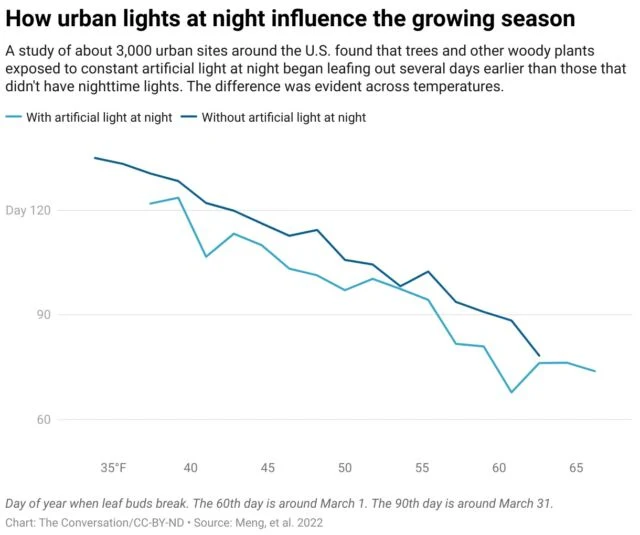

Research team examined trees and bushes at over 3,000 locations in US cities as part of their study to see how they responded to various lighting conditions over a five-year period. Along with temperature, the natural cycle of day and night serves as a signal to plants of the changing seasons.

When compared to sites without evening lighting, they discovered that artificial light alone brought up the date when leaf buds first opened in the spring by an average of roughly nine days. Although the timing of the fall color shift in the leaves was more complicated, it was nevertheless delayed across the lower 48 states by an average of about six days. In general, scientists observed that the difference increased with light intensity.

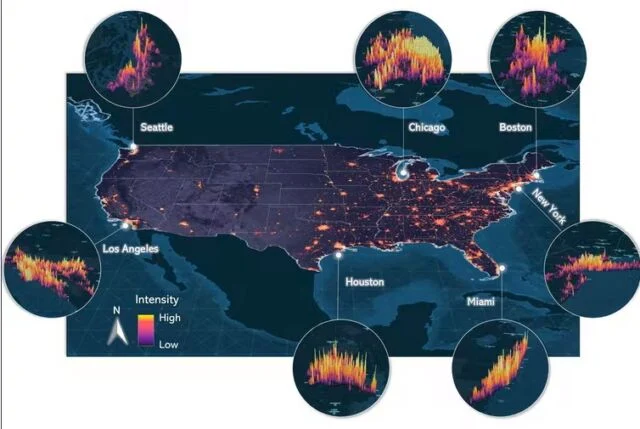

Researchers further predicted the effects of evening lighting on five US cities—Minneapolis, Chicago, Washington, Atlanta, and Houston—based on various future global warming scenarios and up to an increase of 1% annually in the intensity of nighttime lighting. Although its impact on the date of the fall color change was more complicated, they discovered that rising evening light would probably continue to move the start of the season earlier.

Why it matters

The economic, climatic, health, and ecological benefits that urban plants provide might be significantly impacted by this type of change in the biological clocks of the plants.

On the plus side, extended growing seasons could make it possible for urban farms to operate continuously. As global temperatures rise, plants might potentially offer shade to cool areas earlier in spring and later in the fall.

However, adjustments to the growth season can also make plants more susceptible to harm from spring frost. Additionally, it may throw off the timing of other creatures, including pollinators, which certain urban plants depend on.

.jpg)